Chapter 32: Cats and Birds

The great lynx kitten shook itself fully awake when it was time to leave, when the others had turned tail or wing or hoof and the night had begun to draw breath. Sniffing my pink backpack once, it gulped the whole thing down to keep it dry in its stomach. Then it was time for me to ride in the cat’s mouth as it bounded down to the slop to the Reserve’s exit point.

Despite not needing to breathe, the jump in the lake still made me gasp.

The cat swam down, its spines expanding and supporting fins, and its tail pumped once to send me into the water that was deeper than deep, dark beyond my senses and chilling enough to make my fangs chatter. But worst of all was the pressure.

The world turned upside down, and I turned inside out.

Then it happened again, and the great lynx erupted out of the waters of another lake south and west of the Reserve, landing on the shore with me ragdolling and moaning in its mouth, hearing crickets halting their song in confusion in the reeds around us. We were a little closer to Deep River, where another magical cat would lake-hop me to the Land with No Trees (any place with concrete, to these creatures).

Sprinting through the forest to the next lake, I noticed that my mighty steed was preoccupied with the southeast – I had to notice, since every time the cat twisted its head in that direction I flopped around extra hard. I saw nothing unusual over there in the first hour of night, and we made our second lake-jump before midnight, the pressure even worse and forcing a cough of St. Elmo’s indicative fire from my mouth down in the dark. But I didn’t want to complain, seeing as the slightest squeeze of the jaws from the cat would end me – I was still not fully recovered from the tussle with Nocome.

But after the night’s all-encompassing exhale touched my senses, during the sprint to the next lake for the third teleportation, I finally realized what the cat had been noticing about the southeast for quite a while. There was a light grumbling over there, and the growing smell of ozone. That was a thunderstorm.

“What’s over there? Under the storm?” I gasped. It was impossible to say more than three words at a time as the teeth crossed so delicately over my compressed chest. “Tremblant, right?”

YES. The psychic voice was a swift mallet to the inside of my skull. I longed to be huffing on my blood diamond and crashing for another extended period of rest. My body felt increasingly like a rubbery chew-toy, and now I had a headache.

It was very hard to track how much time passed while we were underwater – I felt that it was nearly instantaneous, but perhaps I was just passing out each time. Emerging onto a rocky shore after our third lake-hop, surveying a dark wilderness to the east marred by a strip of powerlines with red warnings lights on the towers, the cat set me down and stood up on its hind legs to glare into the storm. But it wasn’t just a thunderstorm, of course. The anomaly in the sky was now much closer, thundering in the night with a vague outline that my nighttime eyes could just see – until they were temporarily blinded by the first flickers of cloud-to-cloud lightning, which boomed across the land to our ears most of a minute later. I already knew from Nocome that weather was but a plaything for a certain level of power in this land.

“So, you and them don’t get along-”

“At the mountains where lightning strikes, they come,” the cat said, lowing and looking at me. In the night its pupils had swelled, though the eyeball around them was still a golden oven. “You are injured, and will be injured more as we travel, but you must not feed to heal until we have escaped this storm. They do not know our paths, but they can follow the path of a manitou that drinks blood.”

I had said that the cat sprinted between lakes before. “That’s not a sprint,” I said lamely, trying to deal with the rising pain which would be keeping company for a while, trying to speak in the beast’s mouth like Crocodile Dundee. “This is a spr-”

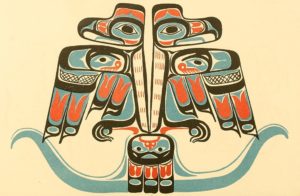

The cat pinched me hard enough to keep me quiet. It was tracking the time between flashes and the rolling thunder as it ran to the next portal to its underworld, away from the surface where a thunderbird might strike.

The next lake to take us somewhere was a brief period of safety. The cat lingered in the unseen depths, and we spoke together. It sensed my pain and eventually lowered its psychic voice.

We and they rule this land, back and forth. What one decides the others would often decide on their own … but when one sees what the other does, there is disagreement.

Fucking politics.

I don’t know those two words, the great lynx replied. If we let a spirit live to walk free like you, the birds might kill. If we decide to kill, they might let that spirit go free. Just for spite, no matter the spirit. If the catch is big enough, they will want it.

So I’m on a big enough wanted poster-

Not you. Nocome. You are just her jar. The birds will want her, and you are easier to catch. We will rise near Deep River, and my brother will swim you faster to the Land with No Trees. But on the way is another mountain that can tremble.

Sinking deep again, we then erupted near Deep River, in sight of the provincial boarder. I looked up into the sky and saw no stars, only continuous lightning in a sky like broken glass.

A second storm from Calabogie! Child of the Eight-Ten, run to Deep River alone! Do not feed!

A giant feline loogie released my backpack, and I tumbled out on the shore, not sure if bones or rocks were breaking below me. The great lynx kitten had extended its spines to resemble a huge hedgehog, mounting a boulder just offshore and roaring upward against the building presence in the sky. In answer a pulse of thunder swept my ears clean of other sounds. It wasn’t even aimed at me, but it made every rib creak.

The journey with the great lynx had already given me barotrauma and shaken baby syndrome atop the general ache that Nocome had left behind, and I was casting my surroundings in a faint glow of purple and green and white as the St. Elmo’s fire wept out of me, seeping out faster at the lines where flesh had just recently pulled together. But I still had my spine – after the ichthys smashed my back had come back a little stronger, and if I made it the Land with No Trees after this night it felt like I would be callused and bulletproof from head to toe.

“Ow ow ow,” I said, running on the stones and setting up a rhythm. “Ow ow ow.”

The rolling hill I climbed was the last barrier between me and the light from Deep River. The town’s lights came across the Ottawa river and trickled away photon by photon into the immense, undeveloped darkness of northern Quebec. There were plenty of animals in these unbothered woods, lots of furry bodies full of blood, but the thirst was just another pain falling into the rhythm.

“Ow ow ow. Ow-”

The flash and the thunderclap seemed to hit me simultaneously from the back, launching me forward, sending me to roll down the hill, banging against tree trunks. I let my pain-rhythm falter as I was slammed onto my back, bent awkwardly over the pack. There was a terrific yowling that rose in pitch to a roar so deep it sounded positively volcanic, and the forest canopy above me swished in unison, all the trees groaning together.

“Ow ow ow. Get up now. Ow ow ow.”

I got up, and hobbled through the woods, chasing the light from across the river. The thunderbirds and the underwater cats couldn’t fight over there – there was a goddamn nuclear reactor on that side, there was science and humanity, there were people with phones who could post it online. It was the sane world that I had known until less than a month ago. No spirits, no cryptids, no haunters in the dark, and I suddenly developed a crazy, delirious certainty: if I crossed the border and made it Deep River, I would be human again. The aura of technology and science would rid me of this goofy nonsense. And in this moment I wanted nothing else.

I picked up my pace. I bled more from my true body, huffing it out like a cloud of condensation. Like a human who is injured and losing oxygen, I soon lost track of what my head was doing.

Instead of reciting prayers in my mind I was reviewing lessons from school. Defining an element, an isotope, the three types of ionizing radiation. The fundamentals of transistors, source and drain and gate, the way to grow boules of silicon, how to dope it with impurity atoms, how to etch it, add a gate, add metal, model it in a computer, how nanotubes of carbon would be incorporated, new dielectrics, cool new materials that I had wanted to play with and discover more of …

So when the forest broke above me, and two great clawed feet plummeted down to take off my head, I was in no sensible mood.

I had been running in a straight line on auto-pilot, chanting my school lessons and regressing, and I screamed up.

“No magic SHIT! Moore’s Law and Kurzweil say progress FOREVER!!!”

They don’t really say that, of course. And this was painfully close to a hopeless nerd trying a ‘Vulcan nerve pinch’ to a bully in school. But my ‘faith’ in the whole technological evolution of humanity from banging rocks to AI gods cruising among the stars was enough to fuel the second spell of my life. A little fly-in-the-ointment spell.

This time the power came out of my eyes and mouth, as I stared up into the giant descending talons. A rush of purple-black wings broken by the hideous electric glow of two white eyes stared back at me, and a huge red hooked beak was blurred with the rush of its downward speed.

Of course humans wouldn’t capture these things on their phones – they’d either be meaningless blurs or they’d annihilate the witness, frying their little toy.

The talons that almost had me swerved, nudged just enough. The beak chopping down like an ax to split my head caught nothing but my left ear, yanking it off. For one incredible moment my leftward glance was directly into a thunderbird’s glaring eye, a white-hot plasma orb that buzzed like a hornet.

The static charge of its closeness didn’t just lift my hair – my hair was tearing out in bloody clumps. My face was contorting into a grimace, and my muscles were clenching uncontrollably as the charges in my body stopped obeying my command.

I flew, quite against my will.

When someone is electrocuted and thrown across a room what really happens is that their muscles all contract simultaneously. The electricity just unlocks the body’s own power. It’s similar to that hysterical strength that mothers supposedly use to lift cars off their kids, breaking all inner restraints for one moment of maximum exertion.

The aftermath of such a full-body flex, of course, is not great. I started feeling the full-body cramp while I was still in mid-air, sailing over the canopy, my eyelids clamped shut, red blood squirting out of the hole where my left ear had been – that wound was superficial enough to merit no St. Elmo’s fire. The cramp, though? I would need a lot more than a rhythm to do anymore more sensible than moan and curse where I landed. And I’d be doing it inside my head, because my throat would be as useless as the rest of me.

Bounce. Another bounce. Apparently I had had a lot of oomf left in me, but the thunderbird’s incidental shock made me use it all up in one great vault. Now I could just notice and count my bounces. I waited for number three, long enough to get impatient.

Splash.

Well … shit. I had made it to the boarder, and not one step further, and if I was human now I was going to drown.

Chapter 33: Deep River

Image credits: D. Gordon E. Robertson, Smithsonian Institute Bureau of Ethnology