Chapter 34: My Summer Vacation

West of Deep River, I stumbled through dense brush in the heat of early summer afternoon. I had gotten lucky with the time of my injuries yet again.

Stopping to open and dry out the contents of my backpack once I found a little clearing etched out for an old covered well, I judged that Marie’s map was just barely recoverable. The Bible she had put at the bottom of the pack still hurt too much to touch and open to see if the ink had run, but I convinced myself that handling it wasn’t quite as bad as before. I was getting a little bit tougher.

Translating into human speak, two competing police forces had squabbled over a prisoner and now that prisoner was walking free. They might not catch him for quite a while, might search far in the wrong places or even think he was dead by the horned snake in the river … though I had no reason to break with the original instructions. I had a monster inside me that would get stronger and stronger after the summer solstice, which couldn’t be far away, just as my own vampiric power above a human’s grew after noon. I had better be in the Land of No Trees before the winter began or else something would come for me – from a deep lake, or from a mountaintop. And I had best not be casual with the major rivers.

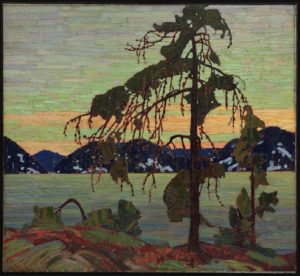

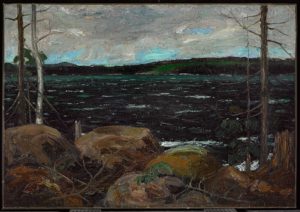

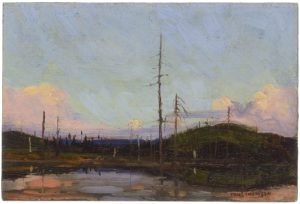

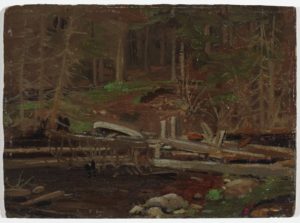

Carefully teasing apart the dried paper of the map, I saw a nice big unpopulated piece of green to the west: Algonquin Park. If I didn’t disturb the spirit of the painter who had drowned somewhere in there I could use that area to hunt, exercise and think for a few days, planning the trip to a longer sanctuary in Toronto. I tried to remember if the painter’s death was a murder or suicide, and couldn’t – I didn’t even know his name, just remembering that it was one of the Group of Seven.

In the late afternoon I passed private homes protected from the roads by marching lines of conifers, and then lonely radio stations and long corridors of felled trees that marked the paths of ancient railroads. Then I slipped through the cottage country just outside the park without incident. No strange storms or cold winds were on the horizon, and my grandmother had finally gone silent.

Helen Forgrave popped herself up into my consciousness like a gopher, and I let her look around and admire all the growing stuff. I let her babble about how northern forests and southern forests met here, making for an extra-diverse patch of land. I liked that – I was learning that for something like me a border between two unchallengeable powers was a workable arrangement.

Out of nowhere I found myself looking at a giant dish in the forest about an hour before sundown. I tiptoed around it, wondering if humans had any of their own secrets that even the spirits didn’t know about.

By sunset on this day – I had completely lost track of days between the multiple bouts of unconsciousness, and would need to find a newspaper to get synchronized – I was inside the park. Nothing challenged me, not even a fence.

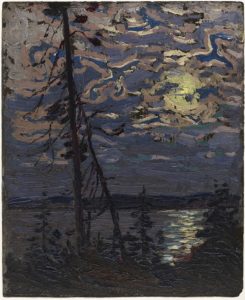

Then night came, and I seemed to have the park to myself. And for the first time in a long while, no one to bug me. Even the bugs didn’t want to touch me, and they were swarming visibly across the lakes in places.

“Ahhh,” I sighed, slumped down upon the shore of a tiny lake free of canoes or docks and napped. When I awoke, just before midnight, I was back to my first days as a vampire: running through the woods, hunting and exploring, and seeing what this new body could do.

I stopped rushing through the woods on my first night when I found a spot in Algonquin Park that passed every sense – no smells, sounds, or sight of humans in the faintest. Clean water, beaver dams, cackling loons, not even any trails that made the area easily accessible by foot. In places the trees were packed like a box of q-tips, and an eight-foot tall ape-man could be unseen a few paces away. Poking my head underwater and yodeling down into the depths, I got no feline answer. It was all excellent. Excellent enough, perhaps, to keep me here until autumn threatened to change the leaves. Then I would jog south, I decided – in a straight line I could hit the northern shore of Lake Ontario in ten days or less.

While the map gave me the right sense of distance it didn’t have the detail for any of these hundreds of little lakes to have a name, and I decided that I didn’t need to find out this lake’s name – any name in English would be a very recent thing.

When day came, I slept. I needed to do that more often, for even after dosing myself with the blood diamond or an animal and getting myself regenerated I still ached, tired in a way that drinking wouldn’t address. I had discovered leaving Trois-Rivieres that I could walk continuously for three days and nights, but it might be a good idea to wait a fortnight before trying that again.

Portions of the map that I had already traveled through became the space for my exercise notes, written in an old golf pencil. My scale of hardness was just the beginning – I might no longer be human, but I was still a bit of an engineer. What came next was some light biomechanics.

TTG stood for ‘Time to glow’, a metric I would collect after every sunset before feeding. I needed one consistent exercise to repeat at max speed until I got through the surface body of blood and stressed the ‘true’ form, extracting that St. Elmo’s fire as an unambiguous indicator. Burpees were supposed to give the whole body some fun, they seemed to be popular with prisoners and I was a member of a similarly untrustworthy community, so I tried some of those. Progress or the lack thereof would show up in this diagnostic number. Maybe.

First night of recording: TTG of 214. Dracula had had the strength of twenty men, but I flatter my human self as being capable of more than 10 burpees before gasping, heart-pounding, let-me-die exhaustion. Maybe I had the strength of about five men right now.

After the first feeding to recover myself I jogged to collect my L score, which came from looping around the lake and was more about endurance than intensity, which I thought the TTG with burpees might catch. I had this one lake as my yard-stick deep in the unmarked country without human smell or sound or footprint. My L score was counted in loops, stopping when I got the glow. But after the fifth night I decided to add one more loop after the glow first showed up. It felt awful – but my run-ins with the birds and beasts had proved that I could do it, so it felt disappointing to just stop when I got the first glow. This wasn’t all about collecting a scientific measurement.

First night: L score of 16, with each loop being a few kilometers. I could still be embarrassed by a few Kenyans.

This was, somehow, becoming fun. Or maybe moping around doing nothing had felt bad enough to demand this distraction. I liked tracking the numbers, trying make sense of them.

I discovered that I could improve my TTG number by about 7 to 10 per night. Ten days in I bumped it up by an extra 15, finally getting past 300. Had I gotten up to the strength of six men?

Well, that would require assessment of my baseline human ability. Burpees and jogging at dawn then, finishing before noon. In those hours I was sweating and panting like anyone working out.

But I discovered that when you know that you will recover from anything – or just about anything that a human can do to themselves while exercising, when you know that sprains and tears and cramps and stitches on the side that rip deep will start to fade away at the strike of the noon – the pain is a lot more manageable. And it was harder to get ‘up to’ that level of pain as the days and nights passed. The daytime exercise was addressing the base level, in video game terms, while the night exercise would perhaps improve the unholy multipliers.

I also discovered that with no job, no school, and no Internet, a 24-hour day is actually a heck of a long time. You can do a lot of burpees in that time. Just like in prison.

This is some sort of ultimate condemnation on our whole fucking system. I’ve been turned into a monster and ostracized to the wilderness with minimal possessions … and I don’t think I’ve ever been happier. No meetings, no appointments, no commute. All I have to do is to get a little harder to kill, each day.

From noon to sunset was strictly designated as healing and sleeping time. Might as well multitask. And I needed to collect the TTG number after sundown while completely fresh.

After burpees I would feed. Feeding a second time after my running around the lake – the odd beaver or muskrat, the slow skunk, an old loon that couldn’t even fly away – would give me a few more hours of free time before each sunrise. I used it to rest, though it was hard for me to really sleep while it was still dark. Helen Forgrave got to use this time to look around and chat all she wanted, and I used it to just stare at a rock or a tree or the eastern sky, resting before my baseline-human exercise routine. I learned to feel the change when my power receded, catching it earlier and earlier.

If Jean-Claude was right, and most vampires were just a bunch of addicts interested in their next hit, this motivated existence might give me a chance in the Land with No Trees. I had been strong enough to handle animals and unprotected humans at just a few days old, and if they were organized enough to avoid tutelaries the civilized vampires to the south might rarely need to exert themselves to feed, and stay soft. If they were all a bunch of pale Edward Cullens picking up blood in bags like milk from a dispensary I might be able to throw the first one I met through a wall and be left alone. Again, prison rules.

But my data was mostly meaningless until I had a second vampire to bump against. My performance and progress had no context … which was good, because complacency couldn’t grow in such an uncertain state of mind. The lack of other tasks kept procrastination from having much success either. (I never realized how unhealthy it was to have an inbox that you could check hourly or worse, keep open for instant notification. Ugh, that was not convenient, that was waiting and wasting time.) I started to have the opposite problem, impatiently waiting for the next part of my routine, because it was hard to just rest and do nothing.

“You know,” Helen told me one dark morning before sunrise, “You should be thinking about making new friends when you meet those new … people.”

“They’re monsters, Helen.”

“You don’t seem monstrous. You were intoxicated when you said all those awful things and fought that terrible bone-lady.”

We argued about drugs that day, silently meditating on a family of loons gliding by on the water as our thoughts went back and forth. Helen said that drugs made you do completely weird things, so they absolved me of responsibility. I was more of the opinion that some drugs would just remove inhibitions, unmasking what was already there.

“Look … if I had been raised by someone else, like in the Mongol horde, I’d be a rapist and a murderer like all of them. And you, sweet grandmother than you are, could sell your children into marriage with monsters like me to ensure the tribe’s future. Or strangle a rival concubine for the khan’s attention in her sleep. I think we just get different filters over the same basic animal nature. I think embarrassment is what keeps a lot of it down, rather than legitimately not wanting those bad things.

“But why aren’t you just eating people at those campsites?” Helen asked. “Your memory says that drinking Jean-Claude felt better than any animal.”

“Too much attention. A tutelary would notice. I’m guessing that the birds and cats think I’m dead in the river, and I’d like to keep it that way”

“I’m in your head, so it’s hard for you to lie. That’s not the only reason.”

I didn’t answer her the rest of the day. She was making my ‘meditation time’ less restful. Maybe if I wanted to try to real thing I needed something more like an isolation tank. The bottom of the lake soon gave me the silence I needed, and the lack of things for the old lady to comment upon.

The pressure down there bothered me less and less each time, and I focused a little harder each time, looking for Nocome. When I found her she was going to get some kind of fight – I had seen parts of the Nightmare on Elm Street films and The Exorcist so I wasn’t totally unprepared for some kind of mind-battle.

Come out come out wherever you are …

But she was hiding good, because it was summer. I needed to sniff her out and have an epic lucid-dream isolation-tank hallucination battle before winter. In autumn I might be a little better at rummaging around my head, and she might be a little too terrible and powerful to go unnoticed.

Inspecting my body without the benefit of a reflection after thirty days of uninterrupted self-improvement, I thought I looked almost the same. Poking my gut, I was still half-soft. Maybe I had to focus more on dawn-to-noon time to get a cosmetic difference.

But the TTG numbers didn’t lie. I was doing six hundred burpees before my true body protested with a little glow. Perhaps I was at the strength of ten men. And if I kept going I could almost reach nine hundred burpees. I had over-exerted myself on day 26, collapsing and losing the time for my jog after my late hunt.

I took that as a sign I was getting too good at this routine. Time to add difficulty. I spent most of day 31 looking for a good rock. I was going to take it underwater and roll it around like Sisyphus. And when the exercise was that automatic I could multitask and meditate at the same time, wearing a groove in the lakebed mud. If the water level ever plummeted the park’s visitors were going to find another one of those ‘sailing stones’ that seem to move by themselves in the desert.

But, like that frog that doesn’t know it’s boiling if the temperature rises gradually enough, I hurt myself terribly the first time with barotrauma. I had overconfidently taken myself deeper than normal, searching for a flatter part of the lake with less sucking mud, and I couldn’t even finish a single loop around the lake with my tumbling boulder that first night.

I took on a little more mud at a lesser depth, and resumed from there. I forced myself to do the math in my head, confirming that pressure would be linear with depth. A quadratic might have killed me.

Let’s say I make it to one hundred years old … eventually, I’ll take a little dip and visit all the famous ship wrecks, saltwater be damned. I hope the Titanic is still recognizable by the time I’m up for it.

More realistically, I would hit a ceiling. At day forty in Algonquin Park my TTG with the burpees had breached seven hundred but lost momentum in its growth, giving me less than ten extra motions per day like my relatively slow start. After several days of the underwater Sisyphus program I was able to hit eight hundred burpees before my glow appeared, bending that ceiling a little bit. But nine hundred seemed very far away. I could feel the damage coming now before I actually bled more than mere surface blood, which was distracting.

When I surfaced after my boulder work started to notice another change to my senses: everything was louder. And brighter. And it wasn’t just the normal disorientation of coming out of a dark room with wide pupils. I needed to spend rest time adjusting to my senses which were growing in the darkness of the deep lake.

Helen had been doing some thinking all on her own. She hit me with an idea while I was hauling my boulder under the lake. My boulder was getting a bit worn down so it was rolling a bit too easily, and soon might crack in two.

“You can handle flowing water due to that ‘water cure’ where you exposed yourself to running water. I’ve noticed lots of those berries that you didn’t like out here, plenty of maple trees with sap, and there are so many different plants in this mixed ecosystem that there must be more than could work as wards against you.”

“Hm,” I said, though I said it underwater so it was more like bwop.

Helen then gave me her personal theory of why kids these days had so many allergies – it was those damn hand sanitizers. Parents were wiping everything clean for their toddlers, not letting them play in the dirt, and eliminating exposure to the environment led to weak immune systems that panicked like green soldiers at the first bit of pollen, causing runaway inflammation.

I agreed that overuse of those hand sanitizers were screwing us over in at least one way – they were selecting for superbugs, just like overuse of antibiotics. Every squirt was filtering the bacteria and letting the strongest emerge from the pile of dead. I admitted that some vaccines might be ‘overused’ and selecting for superbugs in the same way. I wasn’t so sure about her allergy theory, though I agreed to poke around the woods and develop a sort of ‘patch test’ for any suspicious plants, applying tiny amounts in a grid on my forearms with my onboard horticulturalist naming the species. It would be good to know anyway, and if Helen was right it would make future exposure less of a problem. I’d wait and reapply the nasty ones in a second patch test.

I had to put my foot down, however, when she insisted that an overly-sanitized environment was responsible for autism. They had found signs of autism during pregnancy before any vaccine or hand sanitizer, I insisted, vaguely remembering this. I half-convinced her with the metaphor of pirates and global warming – it turned out that Helen had had no formal education after high school, and could use a little scientific rigor.

“You really like to argue,” she said.

“I just hate wrong people,” I said, grinning because I was now out of the water and could hear myself properly. It was fun, to go back to such a ‘normal’ conversation after so much new nonsense.

Poison ivy isn’t good for humans or vampires. Or at least that was my personal vampiric ‘hair colour’, in Jean-Claude’s view of things. I still had some traces of his memory bumping around in my head, and I asked Helen to pick them up and organize them.

Then, more seriously, I asked her if she felt any extra presences. It was somewhere close to the beginning of August and that was after the summer solstice, so any trouble from within ought to be becoming more obvious.

“There are a lot of … rooms. And though the doors are all closed, and most of them are locked, some of these doors have … smells coming out. Like smoke. She must be in one of these little … closets.”

I grilled her for details. Was it like an MC Escher drawing of stairs in there? Could she navigate with a ball of yarn? Was there a way to make keys? But I was basically asking her to go wandering into something at least as vast as the Paris catacombs where there was a monster like the Greek minotaur lurking in the shadows. She was understandably not adventurous and preferred the ‘surface’, where my immediate senses and awareness came in clearly through ‘open windows’.

“Okay, but let me know if any spot feels a little colder than normal.”

“You’re thinking about … something new. I can see that, though I don’t know what about. When you have a new thought the light changes in here.”

I was, though I thought this thought was a little bit too new for the moment, and didn’t give it to Helen just yet (which hopefully meant any lurker in the depths couldn’t hear it either). Helen was alone, but if I had more people in my head, cooperative people who didn’t scream and panic but came willingly through the same process of euthanasia … well, at the very least I could master more subjects than horticulture. At best Nocome might be hunted out and either contained or evicted by my inner army.

But by now it was certainly mid-August. I had been in Algonquin park for almost sixty days, and I could do nine hundred burpees in a row before my true body protested. I could sprint around my yardstick lake until my L score took too much time to collect. I could push my boulder back and forth at the deepest part of the lake and felt the water pressure as little more than a mild pinching. My body was starting to just equalize to the pressure quickly and feel nothing. Poison ivy and wild strawberries and maple sap all hurt me a little less – Helen had been right about that, at least.

Now I had to go. I only had a single season to find the terminally ill, to bargain or fight through their tutelaries to make my army.

Chapter 35: Lampie and Hoagy

Image credits: Tom Thomson (The Jack Pine, Northern Lake, Evening, Old Lumber Dam, Moonlight, Northern Lights)